Sherlock (Sky Context) ∞

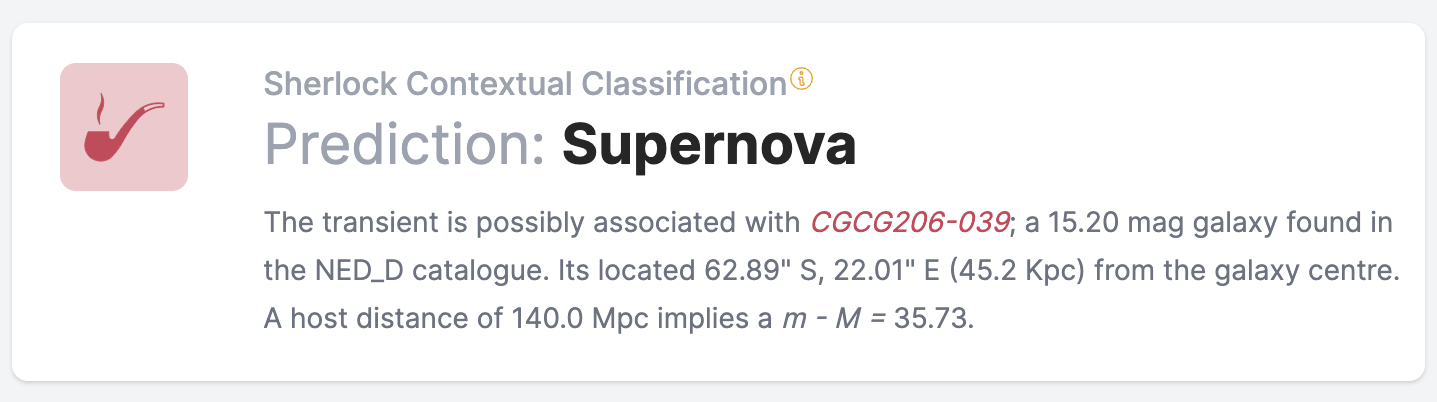

Detections in the input data stream that have been aggregated into objects (i.e. groups of detections) and identified as static transients (i.e. not moving objects) are spatially context classified against a large number of archival sources (e.g. nearby galaxies, known CVs, AGNs, etc). The information derived from this context check is injected as an object annotation The software used is called Sherlock and is discussed below. Here is how the Sherlock information looks on the Lasair object page:

This panel shows a natural language diescription of the association, derived from some of the fields of the Sherlock table:

-|classification: can be any of the 9 strings: NULL, AGN, BS, CV, NT, ORPHAN, SN, UNCLEAR, VS;

in the image above the acronym ‘SN’ has been expanded to ‘Supernova’, which means

that the Lasair object is strongly associated with a host galaxy, but not so close as ‘NT’, which is

Nuclear Transient.

-|catalogue_object_id: is the name of associated galaxy, in this case CGCG206-039.

Not shown in the panel is the catalogue_table_name, which is the catalogue (namespace) of

that name. In this case the name is in the

NED data system.

-|northSeparationArcsec and eastSeparationArcsec for the angualr separation between the

transient and the centre of the associated galaxy. This is translated to physical_separation_kpc

(separation in kilo-parsecs), using direct_distance which is mega-parsecs – if available.

-|Mag is the magnitude of the associated galaxy, using the system in MagFilter. This can

be combined with distance information to derive absolute magnitude.

The full schema for the Sherlock table is in the Lasair Schema Browser.

How does Sherlock work? ∞

Sherlock is a software package and integrated massive database system that provides a rapid and reliable spatial cross-match service for any astrophysical variable or transient. The concept originated in the PhD thesis of D. Young at QUB, and has been developed by Young et al. in many iterations and cycles since. It associates the position of a transient with all major astronomical catalogues and assigns a basic classification to the transient. At its most basic, it separates stars, AGN and supernova-like transients. It has been tested within QUB on a daily basis with ATLAS and Pan-STARRS transients, and within PESSTO as part of the PESSTO marshall system that allows prioritising of targets. It is thus a boosted decision tree algorithm. A full paper describing the code, catalogues and algorithms is in preparation (Young et al. in prep). A summary is included in Section 4.2 of “Design and Operation of the ATLAS Transient Science Server” (Smith, Smartt, Young et al. 2020, submitted to PASP: https://arxiv.org/abs/2003.09052). We label the current version as the official release of Sherlock 2.0. The major upgrade from previous versions are that it includes Pan-STARRS DR1 (including the Tachibana & Miller 2018 star-galaxy separation index) and Gaia DR2 catalogues, along with some adjustments to the ranking algorithm.

A boosted decision tree algorithm (internally known as Sherlock) mines a library of historical and on-going astronomical survey data and attempts to predict the nature of the object based on the resulting crossmatched associations found. One of the main purposes of this is to identify variable stars, since they make up about 50% of the objects, and to associate candidate extragalactic sources with potential host galaxies. The full details of this general purpose algorithm and its implementation will be presented in an upcoming paper (Young et al. in prep), and we give an outline of the algorithm here.

The library of catalogues contains datasets from many all-sky surveys such as

Gaia DR1 and DR2 (Gaia Collaboration et al. 2016, 2018),

Pan-STARRS1 Science Consortium surveys (Chambers et al. 2016; Magnier, Chambers, et al. 2016; Magnier, Sweeney, et al. 2016; Magnier, Schlafly, et al. 2016; Flewelling et al. 2016) and the catalogue of probabilistic classifications of unresolved point sources by (Tachibana and Miller 2018) which is based on the Pan-STARRS1 survey data.

The SDSS DR12 PhotoObjAll Table, SDSS DR12 SpecObjAll Table (Alam et al. 2015) contains both reliable star-galaxy separation and photometric redshifts which are useful in transient source classification.

Extensive catalogues with lesser spatial resolution or colour information that we use are - GSC v2.3 (Lasker et al. 2008) and - 2MASS catalogues (Skrutskie et al. 2006).

Sherlock employs many smaller source-specific catalogues such as

Million Quasars Catalog v5.2 (Flesch 2019),

Veron-Cett AGN Catalogue v13 (Véron-Cetty and Véron 2010),

Downes Catalog of CVs (Downes et al. 2001),

Ritter Cataclysmic Binaries Catalog v7.21 (Ritter and Kolb 2003).

For spectroscopic redshifts we use the

GLADE Galaxy Catalogue v2.3 (Dálya et al. 2018) and the

NED-D Galaxy Catalogue v13.1

Sherlock also has the ability to remotely query the NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database, caching results locally to speed up future searches targeting the same region of sky, and in this way we have built up an almost complete local copy of the NED catalogue. More catalogues are continually being added to the library as they are published and become publicly available.

At a base-level of matching Sherlock distinguishes between transient objects synonymous with (the same as, or very closely linked, to) and those it deems as merely associated with the catalogued source. The resulting classifications are tagged as synonyms and associations, with synonyms providing intrinsically more secure transient nature predictions than associations. For example, an object arising from a variable star flux variation would be labeled as synonymous with its host star since it would be astrometrically coincident (assuming no proper motion) with the catalogued source. Whereas an extragalactic supernova would typically be associated with its host galaxy - offset from the core, but close enough to be physically associated. Depending on the underpinning characteristics of the source, there are 7 types of predicted-nature classifications that Sherlock will assign to a transient:

Variable Star (VS) if the transient lies within the synonym radius of a catalogued point-source,

Cataclysmic Variable (CV) if the transient lies within the synonym radius of a catalogued CV,

Bright Star (BS) if the transient is not matched against the synonym radius of a star but is associated within the magnitude-dependent association radius,

Active Galactic Nucleus (AGN) if the transient falls within the synonym radius of catalogued AGN or QSO.

Nuclear Transient (NT) if the transient falls within the synonym radius of the core of a resolved galaxy,

Supernova (SN) if the transient is not classified as an NT but is found within the magnitude-, morphology- or distance-dependant association radius of a galaxy, or

Orphan if the transient fails to be matched against any catalogued source.

For Lasair the synonym radius is set at 1.5″. This is the crossmatch-radius used to assign predictions of VS, CV, AGN and NT. The process of attempting to associate a transient with a catalogued galaxy is relatively nuanced compared with other crossmatches as there are often a variety of data assigned to the galaxy that help to greater inform the decision to associate the transient with the galaxy or not. The location of the core of each galaxy is recorded so we will always be able to calculate the angular separation between the transient and the galaxy. However we may also have measurements of the galaxy morphology including the angular size of its semi-major axis. For Lasair we reject associations if a transient is separated more than 2.4 times the semi-major axis from the galaxy, if the semi-major axis measurement is available for a galaxy. We may also have a distance measurement or redshift for the galaxy enabling us to convert angular separations between transients and galaxies to (projected) physical-distance separations. If a transient is found more than 50 Kpc from a galaxy core the association is rejected.

Once each transient has a set of independently crossmatched synonyms and associations, we need to self-crossmatch these and select the most likely classification. The details of this will be presented in a future paper (Young et al. in prep). Finally the last step is to calculate some value added parameters for the transients, such as absolute peak magnitude if a distance can be assigned from a matched catalogued source, and the predicted nature of each transient is presented to the user along with the lightcurve and other information.

We have constructed a multi-billion row database which contains all these catalogues. It currently consumes about 4.5TB and sits on a separate, similarly specified machine to that of the Lasair database. It will grow significantly as new catalogues are added (e.g. Pan-STARRS 3_π_ DR2, VST and VISTA surveys, future Gaia releases etc).

The Sherlock code is open source and can be found at: https://github.com/thespacedoctor/sherlock. Documentation is also available online here: https://qub-sherlock.readthedocs.io/en/stable/.

Although the code for Sherlock is public, it requires access to a number of large databases which are custom built from their original, public, releases. The latter is proprietary and therefore would require some effort from users to reproduce. As part of the Lasair project we are exploring public access to the integrated Sherlock code and database information through an API.

Sherlock 2.0 was reviewed as a LSST:UK Deliverable in March 2020. The review noted that an algorithm enhancement would be desirable to take into account stellar proper motions, since some proper motion stars will be variable and if cross-matched with a static catalogue will fall outside the nominal match radius. This is an enhancement we will taken forward for future versions.

Sherlock References ∞

Alam, Shadab, Franco D Albareti, Carlos Allende Prieto, F Anders, Scott F Anderson, Timothy Anderton, Brett H Andrews, et al. 2015. “The Eleventh and Twelfth Data Releases of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey: Final Data from SDSS-III.” The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 219 (1). IOP Publishing: 12. https://doi.org/10.1088/0067-0049/219/1/12.

Chambers, K. C., E. A. Magnier, N. Metcalfe, H. A. Flewelling, M. E. Huber, C. Z. Waters, L. Denneau, et al. 2016. “The Pan-STARRS1 Surveys.” ArXiv E-Prints, December.

Dálya, G, G Galgóczi, L Dobos, Z Frei, I S Heng, R Macas, C Messenger, P Raffai, and R S de Souza. 2018. “GLADE: A galaxy catalogue for multimessenger searches in the advanced gravitational-wave detector era.” Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 479 (2): 2374–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/sty1703.

Downes, Ronald A, Ronald F Webbink, Michael M Shara, Hans Ritter, Ulrich Kolb, and Hilmar W Duerbeck. 2001. “A Catalog and Atlas of Cataclysmic Variables: The Living Edition.” The Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific 113 (7): 764–68. https://doi.org/10.1086/320802.

Flesch, Eric W. 2019. “The Million Quasars (Milliquas) Catalogue, v6.4.” arXiv.org, December, arXiv:1912.05614. http://arxiv.org/abs/1912.05614v1.

Flewelling, H. A., E. A. Magnier, K. C. Chambers, J. N. Heasley, C. Holmberg, M. E. Huber, W. Sweeney, et al. 2016. “The Pan-STARRS1 Database and Data Products.” ArXiv E-Prints, December.

Gaia Collaboration, A. G. A. Brown, A. Vallenari, T. Prusti, J. H. J. de Bruijne, C. Babusiaux, C. A. L. Bailer-Jones, et al. 2018. “Gaia Data Release 2. Summary of the contents and survey properties” 616 (August): A1. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201833051.

Gaia Collaboration, A. G. A. Brown, A. Vallenari, T. Prusti, J. H. J. de Bruijne, F. Mignard, R. Drimmel, et al. 2016. “Gaia Data Release 1. Summary of the astrometric, photometric, and survey properties” 595 (November): A2. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201629512.

Lasker, Barry M, Mario G Lattanzi, Brian J McLean, Beatrice Bucciarelli, Ronald Drimmel, Jorge Garcia, Gretchen Greene, et al. 2008. “The Second-Generation Guide Star Catalog: Description and Properties.” The Astronomical Journal 136 (2). IOP Publishing: 735–66. https://doi.org/10.1088/0004-6256/136/2/735.

Magnier, E. A., K. C. Chambers, H. A. Flewelling, J. C. Hoblitt, M. E. Huber, P. A. Price, W. E. Sweeney, et al. 2016. “Pan-STARRS Data Processing System.” ArXiv E-Prints, December.

Magnier, E. A., E. F. Schlafly, D. P. Finkbeiner, J. L. Tonry, B. Goldman, S. Röser, E. Schilbach, et al. 2016. “Pan-STARRS Photometric and Astrometric Calibration.” ArXiv E-Prints, December.

Magnier, E. A., W. E. Sweeney, K. C. Chambers, H. A. Flewelling, M. E. Huber, P. A. Price, C. Z. Waters, et al. 2016. “Pan-STARRS Pixel Analysis : Source Detection & Characterization.” ArXiv E-Prints, December.

Ritter, H, and U Kolb. 2003. “Catalogue of cataclysmic binaries, low-mass X-ray binaries and related objects (Seventh edition).” Astronomy and Astrophysics 404 (1). EDP Sciences: 301–3. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361:20030330.

Skrutskie, M. F., R. M. Cutri, R. Stiening, M. D. Weinberg, S. Schneider, J. M. Carpenter, C. Beichman, et al. 2006. “The Two Micron All Sky Survey (2MASS)” 131 (February): 1163–83. https://doi.org/10.1086/498708.

Tachibana, Yutaro, and A. A. Miller. 2018. “A Morphological Classification Model to Identify Unresolved PanSTARRS1 Sources: Application in the ZTF Real-time Pipeline” 130 (994): 128001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1538-3873/aae3d9.

Véron-Cetty, M P, and P Véron. 2010. “A catalogue of quasars and active nuclei: 13th edition.” Astronomy and Astrophysics 518 (July). EDP Sciences: A10. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201014188.

https://ned.ipac.caltech.edu/Library/Distances/